After years of dressing down to make the right impression, novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wises up to a truth that her Nigerian mother has known all along.

As a child, I loved watching my mother get dressed for Mass. She folded and twisted and pinned her ichafu until it sat on her head like a large flower. She wrapped her george—heavy beaded cloth, alive with embroidery, always in bright shades of red or purple or pink—around her waist in two layers. The first, the longer piece, hit her ankles, and the second formed an elegant tier just below her knees. Her sequined blouse caught the light and glittered. Her shoes and handbag always matched. Her lips shone with gloss. As she moved, so did the heady scent of Dior Poison. I loved, too, the way she dressed me in pretty little-girl clothes, lace-edged socks pulled up to my calves, my hair arranged in two puffy bunny-tails. My favorite memory is of a sunny Sunday morning, standing in front of her dressing table, my mother clasping her necklace around my neck, a delicate gold wisp with a fish-shape pendant, the mouth of the fish open as though in delighted surprise.

For her work as a university administrator, my mother also wore color: skirt suits, feminine swingy dresses belted at the waist, medium-high heels. She was stylish, but she was not unusual. Other middle-class Igbo women also invested in gold jewelry, in good shoes, in appearance. They searched for the best tailors to make clothes for them and their children. If they were lucky enough to travel abroad, they shopped mostly for clothes and shoes. They spoke of grooming almost in moral terms. The rare woman who did not appear well dressed and well lotioned was frowned upon, as though her appearance were a character failing. “She doesn’t look like a person,” my mother would say.

As a teenager, I searched her trunks for crochet tops from the 1970s. I took a pair of her old jeans to a seamstress who turned them into a miniskirt. I once wore my brother’s tie, knotted like a man’s, to a party. For my 17th birthday, I designed a halter maxidress, low in the back, the collar lined with plastic pearls. My tailor, a gentle man sitting in his market stall, looked baffled while I explained it to him. My mother did not always approve of these clothing choices, but what mattered to her was that I made an effort. Ours was a relatively privileged life, but to pay attention to appearance—and to look as though one did—was a trait that cut across class in Nigeria.

When I left home to attend university in America, the insistent casualness of dress alarmed me. I was used to a casualness with care—T-shirts ironed crisp, jeans altered for the best fit—but it seemed that these students had rolled out of bed in their pajamas and come straight to class. Summer shorts were so short they seemed like underwear, and how, I wondered, could people wear rubber flip-flops to school?

Still, I realized quickly that some outfits I might have casually worn on a Nigerian university campus would simply be impossible now. I made slight amendments to accommodate my new American life. A lover of dresses and skirts, I began to wear more jeans. I walked more often in America, so I wore fewer high heels, but always made sure my flats were feminine. I refused to wear sneakers outside a gym. Once, an American friend told me, “You’re overdressed.” In my short-sleeve top, cotton trousers, and high wedge sandals, I did see her point, especially for an undergraduate class. But I was not uncomfortable. I felt like myself.

My writing life changed that. Short stories I had been working on for years were finally receiving nice, handwritten rejection notes. This was progress of sorts. Once, at a workshop, I sat with other unpublished writers, silently nursing our hopes and watching the faculty—published writers who seemed to float in their accomplishment. A fellow aspiring writer said of one faculty member, “Look at that dress and makeup! You can’t take her seriously.” I thought the woman looked attractive, and I admired the grace with which she walked in her heels. But I found myself quickly agreeing. Yes, indeed, one could not take this author of three novels seriously, because she wore a pretty dress and two shades of eye shadow.

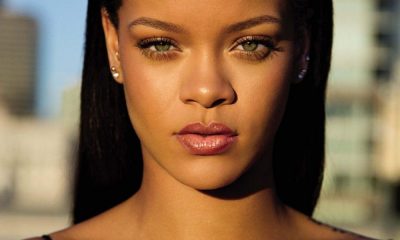

Elle Magazine

Entertainment52 years ago

Entertainment52 years ago

Fitness & Sports52 years ago

Fitness & Sports52 years ago

Articles52 years ago

Articles52 years ago

Beauty52 years ago

Beauty52 years ago

Entertainment52 years ago

Entertainment52 years ago

Fitness & Sports52 years ago

Fitness & Sports52 years ago

Food52 years ago

Food52 years ago

Travel52 years ago

Travel52 years ago